Kinemacolor was a moderate success in the early 20th century. It made millions in Europe but was completely stymied in the U.S. due to the shenanigans of the Patent Trust, an organization of film producers that worked desparately to prevent outsiders from making an inroad in the film business. The Patent Trust was the main reason why independant producers migrated from the U.S. east coast to California.

Kinemacolor was developed in England by expatriot American Charles Urban and his British partner C. Albert Smith. The roots of the system dated back to the work of Edward R. Turner who had received a patent for a three color motion picture system in 1889. Turner enlisted the aid of Urban in 1901, because he was already an important person in the British film business. Research to produce a workable three color system went on for a year until Turner's sudden death in his laboratory.

Urban then called upon Smith to take over where Turner had left off. Several more years of trying to put three colors on the screen failed to yield acceptable results. Ultimately a simpler system using two colors was developed in 1906 and the results were deemed workable. The Kinemacolor system was born. One impediment to producing natural color motion pictures had been the fact that existing film stocks were orthochromatic, insensitive to red light. Until the commercial availability of true panchromatic black and white film in the mid 1920s, color pioneers had to chemically sensitize their film so that it would record more or less of the entire visible color spectrum.

The Kinemacolor camera exposed black and white film through alternating red and green filters. The camera speed was 32 frames per second to achieve the normal silent projection speed of 16 color images per second.

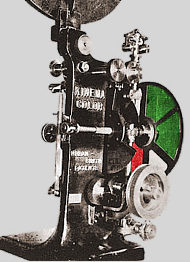

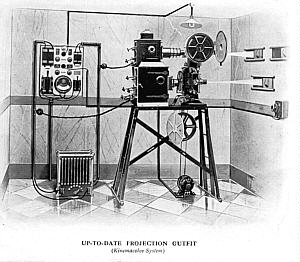

Seen above left is a Kinemacolor camera with the rotating red/green color filter. (The front plate and lens are removed to make the filter wheel visible). Above right is the Kinemacolor projector. Below left is a closeup of the projector, which, like the above illustration, does not include the lamphouse. Below right is an "Up-To-Date Projection Outfit" (Circa 1915). The outfit appears to include a slide projector in addition to power supplies for lamphouses. Note that the projector is seen from the opposite side of the other two images.

Like all sequential color processes, Kinemacolor suffered from color fringing when objects moved, since the two color records were not recorded at the same time. In projection, a filter wheel, similar to that in the camera, added the red and green tints to the successive frames. Many color processes used this approach and all suffered from fringing on moving objects, dark images, and untold grief if the film was not loaded in the projector in appropriate sync with the color wheel. None of the two-color processes could reproduce blue or pure white, but various tricks were used to fool the eye into thinking it was seeing a neutral white.

Seen at left is a current photo of a "new" camera in the collection of Sam Dodge, a big Kinemacolor fan. It's in excellent condition and fully operable. Mr. Dodge hasn't mentioned what feature film he plans to shoot in this pioneering color process.

Below the camera is a closeup of the nameplate that is affixed to the side of the body. Despite the fact that Kinemacolor was a British company, American Charles Urban insisted on using the American and Spanish spelling of "color" rather than the British "colour".

You may view many other historic cameras by going to the Sam Dodge website:

Sam Dodge Cameras (and biplanes) (Opens a new browser window.)

1917 Publication on Kinemacolor

Kinemacolor was one of Technicolor's primary rivals in the period prior to 1920. The frame below is from the successful British documentary color film The Delhi Durbar (1912) which recorded the Indian celebrations of the coronation of King George V. (And don't you just know that all those folks in India were really, really, happy to have a new British monarch. The three people in the film look more like Arizona Indians than Delhi Indians. In fairness to the monarchy, the Durbar celebrated the first time a British monarch had visited the crown jewel of the Empire.)

Above, a pair of frames from a print of The Delhi Durbar and our composite illustrating the color content. In 1912, when this film was made, audiences were enthralled with seeing pictures move. Seeing them in color must have been a remarkable experience. Print image courtesy of Andy Henderson

Kinemacolor was quite successful in Europe and promised to grow and improve. However two events ultimately killed the company. First, William Friese-Greene sued for patent violation. Friese-Greene claimed to have invented virtually everything relating to motion pictures but he lost his suit through all the lower courts in England. He finally did win when he appealed the lower court decisions to the House of Lords. This didn't get Friese-Greene anything but it did open up the Kinemacolor technology so that anyone could take advantage of it. The second event was World War I, which nearly destroyed all the European film companies. By the time Europe started to make a comeback Kinemacolor was nearly defunct and Technicolor in Boston, Massachusetts had taken the lead in producing a workable color process.

New!