This article, of some historic significance, was published in the March, 1953 issue of American Cinematographer. While it is certainly intended to present the best possible aspects of a yet unseen new widescreen process, it is unique in that it does mention certain problems that would have to be overcome to properly utilize the potential of the system. The Robe had not yet begun production when this article was written and you will see that the sound system was three track, with no mention of auditorium surround speakers. The aspect ratio was 2.66:1 since the full silent frame was to be used along with interlocked fullcoat magnetic sound film. No author is credited.

Thanks to cinematographer David Mullen, ASC for providing this and other articles that appear our retro time capsule.

The only added equipment needed in CinemaScope filming is the special lens attached to a regulation camera plus two extra microphones, which pick up sound for the stereophonic sound system.

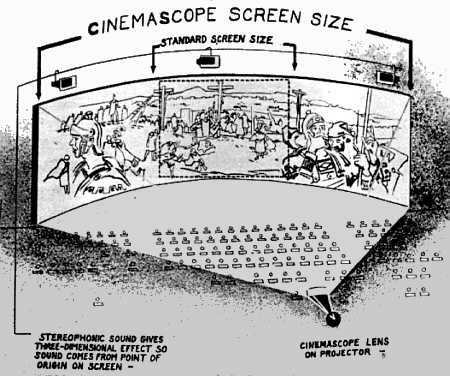

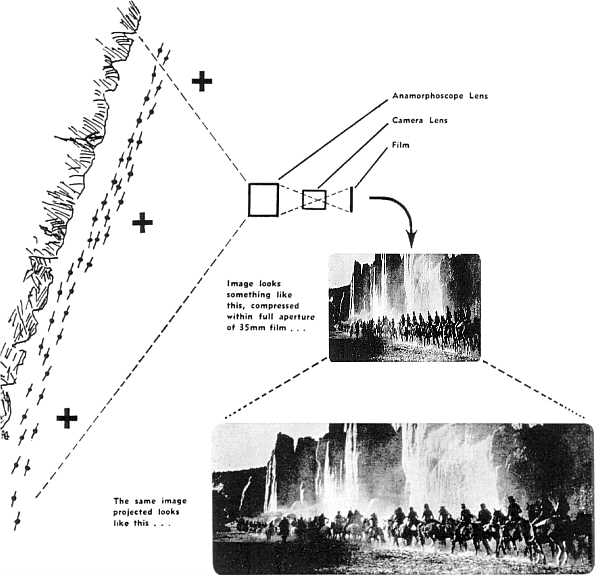

HOW CINEMASCOPE WORKS - Panoramic scene of marching Indians at left is photographed with an anamorphoscope wide-view lens in front of camera lens. This compresses image within the full aperture of 35 film. In projection, another anamorphoscope placed before projector lens expands compressed image to full scale so it appears on screen as shown above, lower right. Three microphones (X) placed strategically to cover the full range of the set or scene record three separate tracks to provide stereophonic sound, an important factor in CinemaScope system.

A UNIQUE LENS which restores to its proper proportions an image previously distorted, makes possible the compression onto 35mm film of wide-angle panoramic scenes, and is the basis of the new CinemaScope system of widescreen motion pictures developed in Hollywood by 20th Century-Fox studios.

When the film is projected through a companion lens the distorted image assumes its former normal dimension, just as a trick mirror in a carnival fun house would straighten out its distorted reflections if placed before a mirror having compensating distortions.

CinemaScope is not stereoscopic movies-not the same as the 3-D films also causing a flurry in Hollywood. CinemaScope films do not require the use of viewing spectacles, do not require special dual motion picture cameras and dual projectors. But the result on the screen, which does present an illusion of three-dimension pictures, is said by many to be superior to 3-D films.

Like the Cinerama process CinemaScope pictures are panoramic and have stereophonic sound. The wide screen used for CinemaScope is a solid screen having great reflectance, and is curved slightly but not to the extent of the Cinerama screen.

HOW CLOSEUPS WILL BE COMPOSED in CinemaScope wide-screen photography. Tight closeups will probably be avoided in favor of head-and-shoulders composition with the figure or figures placed a little to the left or right of center of the frame, as in this sketch of a scene for "The Robe," 20th-Century-Fox's first CinemaScope production.

CinemaScope is a simple, inexpensive process applicable to either color or black-and-white films, which simulates three-dimension to the extent that objects and actors seem to be part of the audience, while its stereophonic sound imparts additional life-like quality as it moves with the actors across the screen.

From its panoramic screen, two and a half times as large as ordinary screens, actors seem to walk into the audience, ships appear to sail into the first rows, off-screen actors sound as though they are speaking from the wings.

CinemaScope is a simplified improvement of an anamorphoscope lens (which he called a Hypergonar) developed by Frenchman Henri Chretien with whom 20th Century-Fox recently closed arrangements for its use and other patented improvements.

(Ed. Note: Webster's dictionary defines anamorphoscope as: "A cylindrical mirror or lens which restores to its normal proportions an image distorted by anamorphosis.")

The anamorphoscope is fitted before the regular camera lens and functions to gather up a wide field of view and funnel it, compressed, through the camera lens, leaving a distorted image of the scene on the film. In projection, a similar anamorphoscope placed before the projector lens unscrambles the image so that it reaches the screen exactly as filmed and completely without distortion.

In describing the Hypergonar anamorphoscope lens. Chretien said: "The Hypergonars which we have built are of two types: for photography, and for projection They differ only in their dimensions and their mountings."

From the optical point of view, they consist of two separately achromatized systems: a converging system consisting of two lenses, cemented together, and a diverging system consisting of three lenses, cemented together.

In photography, focusing of the anamorphoscope is accomplished in accordance with the distance of the subject, by means of a spiral-shaped shaft and the help of a distance calibration. This does not alter in the least bit focusing of the camera lens.

PROJECTION OF CINEMASCOPE movies requires but one projector. Screen is curved slightly and fills entire stage proscenium, Three speakers-one in center and one at either side of screen (i.e., behind it) reproduce the stereophonic sound track, lending added naturalness and dimension to CinemaScope movies.

In projection, Chretien explains, the Hypergonar is adjusted once and for all in accordance with the distance of the screen, by means of a helical rack and pinion. The interposition of the Hypergonar does not modify the definition on the screen.

The loss of light occasioned by the introduction of the anamorphic attachments is insignificant, the inventor points out, because the consecutive interposition of only- two supplementary lenses, i.e.. the two Hypergonar units, consists of cemented lenses. In addition, the exterior surfaces of the elements in each system are treated with anti reflection coating. In projection, the screen brightness is reduced proportionately - to the enlargement of the anamorphic attachment, since there is a larger screen area to light, and not in proportion to its square (as would be the case where the image were enlarged in all directions).

CinemaScope requires only one camera for filming and one machine for projection on the screen. It utilizes the same cameras and projectors now standard in all studios. And because the anamorphoscope lenses can be adapted to all makes of 35mm cameras, 20th Century-Fox expects to make the CinemaScope system available to all motion picture studios.

CinemaScope poses few problems for the director of photography. Use of the CinemaScope attachment on the camera, it is reported, does not alter the exposure time. One minor change, in addition to the auxiliary lens, will be that of enlarging the horizontal scope of the camera viewfinder so that it will be possible for the cameraman to see the actual area taken in by the anamorphoscope auxiliary in front of the camera lens. The wide-range viewfinder viewing glass will have two vertical cross hairs which delimit for him the field of the ordinary screen (or standard aperture) inside of which he may assemble the elements of action when it is desired to present the action in the ordinary manner.

Checking the scene directly through the lens will present something of a problem because what the cameraman sees through the lens will be an optically compressed scene, the same as will be registered on the film. Because the stereophonic sound tracks of CinemaScope films will be separated from the picture film, the picture will occupy the full width of the 35mm aperture. In most cases, the 3-dimension sound will be recorded on magnetic film, in three separate tracks, as picked up by three microphones placed strategically in or above the set.

Although closeups are reproduced dramatically in CinemaScope films, fewer may be needed because medium shots of actors in groups of three and four show faces so clearly that the most minute emotions and gestures are obvious.

In the beginning, it is likely that most CinemaScope productions will be basically outdoor spectacle dramas. This will go a long way toward solving the lighting problem-which undeniably will be great when it comes to shooting the large wide-angle sets indoors on the sound stage. Also, it is likely there will be less emphasis on effect lighting, admittedly not so important where films are shot in color.

CinemaScope poses a number of problems, too, for the film editor. One studio cutter said CinemaScope will make necessary a special horizontal enlarging lens for Moviolas, which will enable cutters to view CinemaScope film with the image fully unscrambled or rectified. Film cutting problems in the new medium, he said, will not be as great as was at first expected because there won't be as many cuts in CinemaScope films as with standard productions. C-pix will be like stage plays where the spectator visualizes closeups and medium shots when he focuses his individual attention on the principal player or some specific bit of action.

Where closeups are necessary, he went on to say, it is likely that these will be photographed with the player just a little to the right or to the left of the frame center-not too far to one side nor with part of the frame blacked out, as has been practiced in some other wide-frame systems.

The cutting of the stereophonic sound tracks, perhaps, will pose one of the greatest problems for cutters, for unless the scene is properly composed both for sound and picture, cuts may occur at the very highpoint of, say, dialogue coming from the extreme right of the screen, with sound for the succeeding cut jumping back to the extreme left of the screen.

In the beginning, film editors will have to feel their way cautiously, as indeed will all other technicians. There will be a greater need for unstinted cooperation between the production planners, the director, cameraman and cutter, in order to effect the smoothest possible result on the screen.

Of great importance to the viewer, there is no distortion of images in CinemaScope pictures from any seat in the theatre. Screens, specially developed for the new system for extra brilliance, may be any length desired to fit any theatre. The screen used for projecting tests at 20th Century-Fox studios is 61 feet wide and 25 feet high. A theatre like New York's Roxy would probably use one 80 feet long with proportionate ratio of height to width. The screen curves to a depth of five feet-enough to afford a feeling of engulfment without reflecting annoying highlight from one curved end of the screen to the other, as deeper curving screens are said to do.

Due to the immensity of the screen, few entire scenes can be taken in at a glance enabling the spectator to view them as in life or as one would watch a play when actors are working from opposite ends of the stage.

Commenting on CinemaScope, following a series of test screenings at the studio, director of photograph Joe MacDonald, ASC, said: "People will see things they've never seen before. When you look at CinemaScope it's like taking off blinders. It gives all the three-dimensional feeling that people want. Every cameraman that I've talked to is enthused about CinemaScope because it will enable him to make a more substantial contribution to story telling. Scenes will be longer and more intricate."

Supervising Art Director Lyle Wheeler had this to say: "Thanks to CinemaScope, sets will play a more integrated part in the picture than ever before. Just as on the stage, width, not depth, will represent the typical setup."

The sound implications of CinemaScope are as important as the visual ones, believes Lorin Grignon, 20th's sound engineer, who worked closely with Sol Halprin, ASC, and other studio engineers in perfecting the system. "In bringing stereophonic sound to the screen," said Grignon, "the illusion of reality will be conveyed to a degree never before realized."

Editors will be able to deliver smoother pictures with CinemaScope because scenes will be longer and there will be fewer cuts and closeups, according to 20th's film editor William Murphy.

It appears that CinemaScope will make special effects photography more important to film production than ever before. Matte shots will be widely used and there is the possibility that such shots will be the answer to the building of vast panoramic sets where the action must be staged indoors on the sound stage.

Ray Kellogg, who heads the special photographic effects department at 20th Century-Fox said, "With CinemaScope, special effects will bring greater realism than ever before. To me, CinemaScope is more important to the industry today than was the advent of sound in its day."

ONE OF THOSE most instrumental in the perfection of Twentieth Century-Fox's CinemaScope process is Sol Halprin, ASC (center) studio's executive director of photography. Assisting him were (I to r) Lorin Grignon, sound engineer; Wm. Weisheit, chief projectionist; Grover Laube, camera engineer; and Carl Faulkner, sound department.

CinemaScope is ideally suited to spectacle films in which most of the action can be played against huge outdoor panoramic vistas. Twentieth Century-Fox has chosen "The Robe" as its initial production to be made in CinemaScope, which will be photographed under the direction of Leon Shamroy, ASC. As soon as the key sets are constructed, shooting will get under way, which will be about March 4. Shamroy has worked closely the past month with Sol Halprin, head of Fox's camera and laboratory departments, and the man most instrumental in the development of CinemaScope for the studio. Exhaustive tests have proven the system perfect in every way, and according to a studio executive, all that remains to make CinemaScope an established big-time thing in industry is volume production of CinemaScope lenses. Twentieth Century-Fox, which holds world rights to the system, except for France and its colonies, expects to have between 3,000 and 5,000 sets of CinemaScope lenses available before the end of 1953.

END

As an added bonus, I am including this small sidebar article that appeared with the CinemaScope text. It chronicles the availability of an anamorphic system marketed in the U.S. in 1931.

Anamorphoscope Lens Not New -- Goerz-American

Marketed One For 16mm Movies Back In 1931LIKE STEREOSCOPIC MOVIES, which are now sharing the spotlight along with CinemaScope, wide screen movies are not a new discovery. As with stereo movies, they have simply been rediscovered after having been introduced publicly - about 20 years too early. The C. P. Goerz American Optical Company placed on sale in the early thirties the Staats-Newcomer-Goerz "Cine-Panor" lens for 16mm movies, which the company stated then "takes and projects a 50% wider picture."

The lens was the development of Dr. Sidney H. Newcomer, a New York physicist and mathematician. Describing the lens in an article in the American Cinematographer for May, 1931, Fred Schmid, then vice-president of Goerz, stated: "This new lens consists entirely of cylindrical lens elements instead of spherical lenses of the regular photographic lens. It does not produce an image by itself, but has to be used in conjunction with the regular photographic lens of the camera when taking wide-field pictures. In the same way the same lens must be used in front of the projection lens when screening the films photographed with it . . . This same principle of producing wide-field screen pictures with standard 35mm cameras and projectors can be adapted for the professional screen as well by making the auxiliary lens system of suitable size. That it hasn't been done is most likely due to the uncertainty in the minds of motion picture producers whether, under present economic conditions in the motion picture industry, the time is opportune for introducing this new feature." (There was a depression on at that time, remember? -EDITOR).

Despite the potential promise it held, the Cine-Panor, it is reported, was withdrawn from the market shortly afterward due to some patent difficulties. It is understood, though, that Dr. H. H. Newcomer retains control of the same lens system for 35mm films.

Transcribed and edited by American WideScreen Museum - HTML Copyright ©1998