Gordon McLeod,

G.A. McLeod Enterprises,

Toronto, Ontario

Horizontal VistaVision Projector

The Complete Story of How the Projector for the Showing of Horizontal

VistaVision Was Designed, Developed and Put in Use in Only Four Weeks

BY LARRY DAVEE

Century Projector Corporation

Brief: The full and sometimes amazing story of how the author, and his organization, answered the demand for a horizontal projector mechanism is described in this interesting article. Compressing what is normally a one or two year project into one month, the development of the equipment for the showing of horizontal VistaVision is a wonderful example of how the industry has geared itself to meet the demands of the new projection systems. In addition to this background information the reader will find a thorough description of the projector mechanism, with full explanations of how and what each component part has been designed to accomplish. There is a valuable discussion of the problems of heat and light, and how this mechanism combats them. There is also important information about theatre sound and what is accomplished with the horizontal projector. Data on how the mechanism can fit into new and already existing projection booths is furnished. This is a story worthy of close reader attention.

The design of a new projector mechanism normally involves between one and two years of engineering work-and this time they wanted it done in four weeks. They wanted a miracle. And-miraculously-they got it.

"They" in the present instance were Paramount's technical chief, Loren L. Ryder, and his organization. What they wanted in four weeks was an utterly new, unprecedented, horizontal-type projector for VistaVision. The demand was absurd. But they said the show had to go on.

Experimental Work

Behind this most unreasonable request was some experimental work Ryder and his group had done on the Paramount lot previously. They took an old, abandoned motion picture camera-one built by William Stein back in 1926 and shelved ever since-modernized and altered it, and put it on its side and took pictures with it that way. They had no projector for showing the pictures so they took one of our mechanisms, a Century CC model, and laid it on its side and ran the new picture that way-ran it backwards, in fact. But the quality of that queer showing indicated to Ryder and his fellows that the basic idea was sound and further development worthwhile.

Not only were the Paramount people unequipped for proper viewing of their own work but Technicolor, which made the print, had no means of inspecting it after it was made, except by sending technicians to the Paramount lot to look at it through Paramount's make-shift set-up

Projected as Photographed

VistaVision, as every theatreman knows by this time, is made to be projected in several ways, one of them through a squeeze print in a conventional, old-style projector. But the greatest value of VistaVision, its real value, cannot be realized that way. For best results the VV print should be projected as it was photographed, horizontally. And not through the haywire device of an ordinary projector placed on its side but through a proper mechanism made for this type of work. Besides, even if the projector-on-a-side, could give suitable results, which it can't, there simply is not enough lateral room in most theatres to install mechanisms with their magazines reaching left and right, instead of up and down. Moreover, in this case the magazine must be oversize since the film spec. is 180 feet per minutes instead of 90 feet per minute, and 4000-feet magazines instead of the 2000-feet size are needed for a 20-minute show.

Now all this was in 1954 and Paramount had "White Christmas" all beautifully photographed via Stein's once forgotten 1926 camera, and they wanted to project it for a paying public, on non-existent horizontal projectors, during Christmas week of 1954! We Century-would kindly produce those projectors, complete and ready for use in four weeks!

How do you produce something that has never existed, solve problems, iron out "bugs" all in four weeks?

The truth is, Century did it, and is still gaping, wondering how. We did it though, and the show went on. We completed six mechanisms. Two went into Radio City Music Hall in New York, two into the Warner Theatre at Beverly Hills, and two to the Paramount lot.

Basic Necessities

You can say that those six mechanisms were crude, and you can say it again. They did not even have doors-they were open, like European mechanisms. There was no time to bother with doors. There was no time to bother with anything except basic necessities. There wasn't even time to draw assembly prints. Our factory people assembled those six machines without assembly prints-with nothing to go by but detail prints. Of course, they were our top mechanics, with plenty of experience with projectors; no one else could possibly have been assigned to such a zany job. But even so, to assemble working equipment with no assembly instructions is perhaps one for the engineering colleges to think about.

The four-week wonders thus manufactured turned in outstandingly successful performances in two of the most important theatres in the world.

And the two mechanisms that went to the Paramount lot gave Paramount and Technicolor engineers their first chance to see their own work with the picture properly presented, not running backward.

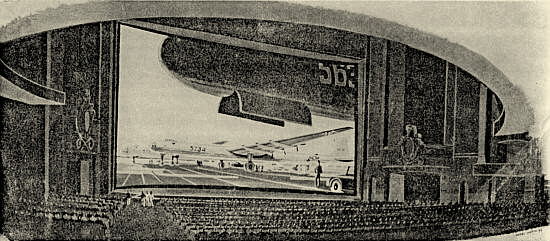

FIG.1 shows the horizontal projector with the drive motor, the framing knob, the changeover mechanism above the projector. The projection arc lamp used is located in the rear of the unit. Standard projector below.

Redesign

Then we redesigned and within the next few months we built and delivered these redesigned Century VistaVision horizontal projectors for many installations. "Strategic Air Command" was shown on the large screen, by horizontal projection, at an Omaha Air Force Base before it opened at the New York Paramount "We're No Angels," "Seven Little Foys," "To Catch a Thief," and other VV features followed quickly one after another. Paramount and other producers finally got built-to-order cameras and returned the Stein to a well-earned retirement. Short subjects also began to appear in VistaVision and Century's production of the unprecedented horizontal projector mechanisms kept pace with the demand.

No "Bugs" Develop

To me, one of the many wonders of the whole incredible business is the fact that these completely new mechanisms, designed in a hurry, built in a flash, have developed no "bugs." This is very nearly unbelievable; all new equipment develops faults that don't show up on the drawing boards or in the testing room, but only in practical use. Almost all new mechanical equipments of any kind-automobiles no less than projector mechanisms-tend to develop unpredicted, unforeseen troubles in each new model, and must be modified after the first models have been sold. Our horizontal projector mechanism is not only new, but original; there has never been anything like it except possibly one of Thomas A. Edison's earlier abandoned, experiments. It was both designed and produced at unprecedented speed, yet our "bugs" have been almost zero. I can only account for this by the fact that we have been designing and building projection equipment for so many years, and our people have so much concentrated experience, that they almost instinctively apprehend and avoid a "bug" as they go along.

Standard CC and C models have been giving exhibitors satisfactory and pretty "bug-free" service these many years; but those models were not designed in four weeks, nor assembled without prints, nor installed in commercial use without engineering tests, life tests or any other kind of tests. What Paramount wanted for VistaVision was either a miracle or a near-miracle, and we gave it to them.

The advantages of VistaVision in horizontal projection are abundantly visible now on the screens of many theatres. But not all of the advantages are on the surface. The hidden values are perhaps as important as those that are visible.

Hidden Values

For example, the industry urgently needed larger screens, and VistaVision among other systems, made them possible. But more light is needed for a larger screen. Spread the same light over a larger screen and all you accomplish is to dim the picture. The problem and difficulty of getting more light is fairly well known. More light means more heat. Most of the electricity burned in the projection lamp unfortunately produces heat. Only a comparatively trifling percentage of the energy appears in the visible spectrum, where it is wanted. The rest is concentrated in the infrared and is definitely not wanted, but must be tolerated.

The rest of the problem lies in the fact that the film refuses to tolerate the heat. The film curls up. It loses its smoothness and flexibility and becomes horny-corrugated-buckled-baked out. Such film is spoiled because the pictures on it can't be focussed. If the raised areas are brought to focus by adjusting the projection lens the valleys will be out of focus, and vice versa. And film once buckled can't be restored; it is good for nothing but to be thrown away.

Combat Heat Problem

Many answers have been worked out for this problem of getting enough light for the larger screen without buckling the film. We at Century were among the pioneers in this. The answers consisted essentially in cooling. This partial solution, there will never be a complete solution until somebody produces cold light, of cooling is applied in a number of different ways at a number of different places. Both air cooling and water cooling are used; and for air cooling both steady streams of air and pulsed streams. Water cooling is sometimes applied to the carbon jaws of the arc. Sometimes a heat filter is inserted in the light path ahead of the film protecting the film; but the heat absorbed by the heat filter must go somewhere, and to keep the filter from cracking air cooling is applied. Projector film apertures are water-cooled. All cooling helps, but VistaVision's horizontal large-frame projection contributes further help which is not dependent on cooling.

Size Reduces Problem

To understand this further and different help contributed by VistaVision it is only necessary to remember that all projection lamps act like a burning glass in that they contain optical elements which focus the light (and therefore the heat) on the small area of one film frame. But in the case of VistaVision the burning glass effect is reduced because the VV film frame is so much larger. The conventional projection frame measures 0.4950 square inches (0.600 by 0.825) whereas the VV horizontal projection frame is 1.467584 square inches (0.997 by 1.472). Modify these figures very slightly to make the conventional frame area 0.5 square inches, and that of VV horizontal projection 1.5 square inches. It will then be seen at a glance that the VV frame area is essentially three times as large as that of conventional projection, and therefore will permit use of a screen three times the previous size before resorting to cooling of any kind. Now, when cooling is added (and the VV Century-built horizontal projector mechanism is fully equipped for water-cooling of the aperture) it is evident that doors have been opened to an enormous advance in screen size. In addition, Paramount recommends (and we agree) that advantage be taken of the further benefit inherent in using water-cooled projection lamp jaws also. When a larger screen image is obtained by optical expansion of a film frame that is of conventional size or nearly so, the burning-glass effect continues as in the past to limit the amount of light that can be used to that which the film can endure without buckling. Aperture cooling and lamp jaw cooling still help with any size aperture, but the maximum increase in screen area only becomes possible when the film frame is both artificially cooled and also larger in dimensions.

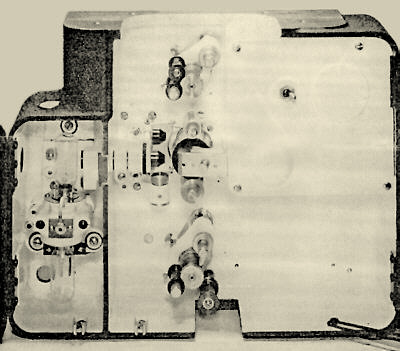

FIG 2 illustrates the way film changes course from vertical to horizontal and back to vertical again, as required by this system.Compact Mechanism

One of the most important practical facts about the horizontal projection mechanism is its compactness. This horizontal mechanism occupies no more space than a conventional vertical projector mechanism. It can be installed in any theatre regardless of limited front wall space because it takes up no more room than the equipment that is installed there now.

Of almost equal practical importance is the fact that the mechanism can be installed on any standard American projection pedestal. Separate pedestals are available and of course many theatres (especially those with enough front wall space in the projection room) prefer to add a complete VistaVision installation to the equipment they already have, rather than disturb their conventional installation. But other theatres simply take off their existing projectors and soundheads, leaving the lamphouse and pedestal as they were, and put on this VV projection and sound apparatus instead. The choice is a matter of available front wall space first of all, and after that of economics and of program planning.

Film Runs Up

The path followed by the film is exactly the reverse of conventional. Film does not run down; it runs up. Film speed is twice normal-180 feet per minute instead of 90.

The full new reel is placed in the lower, not the upper, magazine. The film enters the soundhead before, not after, it traverses the projector. The soundhead can be seen at the left of the horizontal mechanism, just above the lower magazine. On emerging from the top of the soundhead the film takes a half-turn and enters the horizontal projector, crossing it from left to right (in this illustration) and passing horizontally before the projection lens. On emerging from the right side of the projector proper the film takes another half turn and runs upward into the upper or take-up magazine.

Seen in the illustration (Fig. 1) are the drive motor, the framing knob just above the drive motor, the changeover mechanism above the projector, and the projection lamp at rear.

Changes Course

Also illustrated here (Fig. 2) is the way the film changes course from vertical to horizontal and back to vertical again. At left the film is seen coming up from the soundhead and then taking a half-turn course, and running around what may, perhaps, still be described as the "pull-down" sprocket, although it pulls up and laterally and we call it the projector feed sprocket. Just above this sprocket (pictorially above it, that is) the film proceeds through its "upper loop," then rightward through the gate to the intermittent sprocket; then through its "lower" loop to what we call the intermittent loop stabilizer sprocket Then the film again takes a half-turn into a vertical course and proceeds upward to what we call the hold back sprocket and the upper (take-up) magazine.

The film compartment, as this same picture shows, provides abundant room for the projectionist's fingers in threading the film into place, making the proper loops and completing all adjustments; it is amply illuminated by two lamps, and its interior is white-enameled both for added illumination and to show up, and encourage removal of, dirt or emulsion crumbs.

An Innovation

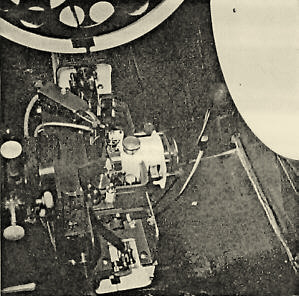

The film compartment includes an innovation-an industry "first"-the use of ball bearings in the pad rollers (Fig. 3). These rollers rest against the sprockets; they hold the film in engagement with the sprocket teeth and prevent it slipping off the teeth; they rotate with the film motion, but they have never before been ball-bearinged. Here is precisely one of those possible "bugs" I mentioned previously-the kind of trouble that does not necessarily show up at all in manufacturers' tests. Film formerly ran at 90 feet per minute. In VV horizontal projection it runs at 180 feet per minute. Would the pad rollers give trouble at the increased speed? There was no way to find out short of prolonged testing because they might not give trouble at first when new and round, but only afterward when they had become somewhat worn through extended use. But we have been making projectors for a long time and our people sensed that possibly here was a place where trouble could show up - later on, not immediately - and we felt that the relatively trivial cost of putting in ball bearings was an abundantly justifiable insurance. So we put in ball bearings. It is a step representative of the same general principles we have followed throughout.

Power

Power is applied to the mechanism through Gilmer belts. These belts have gear-shaped corrugations along their inner edges, and they run on geared pulleys, not on ordinary ones. They cannot slip at all as ordinary belts do, and for that reason are called Gilmer timing belts. They do, however, have some of the flexibility of belts, which drive shafts and chains do not have; they tend to damp out and not to transmit vibration, because of their flexibility; they are long lasting and decidedly economical. Three of them are used in the horizontal projector. One transmits power from the drive motor to the projector mechanism, and by its resilience practically eliminates motor vibration. A second carries power to the hold back sprocket above mentioned, and a third drives the upper or take-up magazine.

Power transmission within the mechanism and the soundhead follows the simple single-shaft system that has proved so successful through the years in conventional Century projectors There is one straight power shaft, belt driven, which drives the sprockets, the intermittent movement, the shutters, the governor and the soundhead.

There are two shutters, which lie between the film and the lamphouse, and by their location contribute still further to the amount of light that can be used without damage to the film, since during those intervals (48 in each second) when the screen is momentarily dark, the film is dark too and unnecessary heat does not accumulate at the aperture.

High Sound Quality

The sound that accompanies VistaVision is, as most showmen know by now, not only simplified but highly improved. Because of its simplicity it combines extremely high sound quality with low cost; and like the picture, the sound is available in several price ranges. As the best picture, in our opinion is the horizontally projected VistaVision, the best accompanying sound is the three-dimensional (not stereo) Perspecta Sound; and our soundhead is fully designed to get the very finest out of the film that the studio put into it.

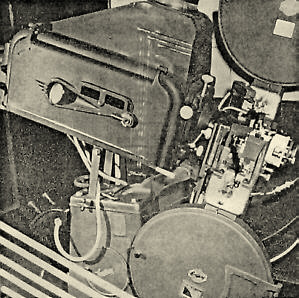

Film runs up in the sound head and not in normal downward direction

Flutter Suppressor

As in the case of the projector, so with the soundhead, we had problems to solve in a rush, but we did solve them. They centered essentially on our flutter suppressor, which has always been better than good - 0.08 per cent flutter content where the Academy standard flutter minimum allows practically twice that; 0.15 per cent flutter content. Now, however, we faced the problem of making our flutter suppressor perform equally well not only at twice the former film speed but also against gravity where in the past applications it worked with gravity. The whole suppressor mechanism had to be recalculated, to the same formula as in the past, but to new conditions. And the new parts had to be built, and assembled without assembly drawings and put into commercial use without engineering tests. After the equipment had been put into theatres and was working for paying spectators, we made flutter tests in the theatre, and established beyond doubt that our new flutter performance is as good as in the past - 0.08 per cent flutter content, just as in our model CC.

Doubles Speed

The superiority of Perspecta Sound, however, derives essentially from the fact that the film runs at double the former speed. Flip any phonograph record to make it run faster momentarily and you will hear the pitch of the sound jump a bit. The striations are passing under the needle faster; the needle is vibrating a little faster, and the pitch of the sound goes up proportionately. The frequency content of any phonograph recordings could be increased by making them and playing them at greater speed; and as you know the phonograph speed for many years was 78 rpm. With more modern record materials it became possible to get the striations smaller, crowd more of them into a given space; so it was no longer necessary to run the record as fast as before and record speeds came down to 45 and 33 rpm.

But in photographic soundtracks it has never been found practical either to reduce the striation size or to narrow down the light beam (which may be compared to the needle point in phonographic sound). It has never been found possible to reproduce more than about 9,000 cycles of sound, if that, with reasonably full volume under the old conditions. And as hi-fi record players, frequency modulation radio broadcasting, and other improved sound reproducers came into common use, the theatre, which at one time offered the best sound available, fell back by comparison, and at its best did no better than the customers could get from a hi-fi platter spinner at home.

Just as the screen had to be enlarged and brightened to compete with the television picture in the living room, so also sound needed to be improved to help it compete with the hi-fi record player and the fm radio.

Sound Frequency

Reproduction Increased

The VistaVision-Perspecta Sound film that runs at double speed has the effect of doubling the upper limit of sound frequency reproduction. An upper limit of 16,000 cycles is the maximum necessary; few ears can go higher than that and most ears cannot reach it; 8,000 cycle reproduction from conventional film is increased to 16,000 cycles with VistaVision film, and that problem is solved-at least, as far as concerns the soundhead. What the amplifiers and speakers do with this improved sound after it has been delivered to them is another story.

Our VistaVision-Perspecta Sound reproducer head is pictured here (Fig. 4). Only the upper exciter lamp works since the lower one is a pre-focussed spare. The lens tube is seen aligned with the upper lamp filament, and the sound drum, which holds film flutter down to half as much as even the Academy permits, is aligned just right of the lens tube. Film runs through this soundhead in an upward direction as already explained, not downward.

The pre-focussed spare exciter lamp serves the cause of economy as much as anything else; modern exciter lamps do not burn out very often, but they do of course burn out. Any projectionist who is doubtful of the condition of his lamp will be inclined to replace it, not taking chances with his show for the sake of a lamp bulb, but if he has a pre-focussed bulb in the soundhead, available at the flick of his wrist, he will be less inclined to discard lamps that probably have a good bit of life still left.

The soundhead film compartment, like that of the projector mechanism, is amply and abundantly large enough for careful and accurate threading of film, and white enameled for visibility and cleanliness.

VistaVision and Perspecta Sound are, of course, furnished by the producers to the choice of the exhibitor. They can be obtained in conventional prints, with conventional frame dimensions, run in conventional projectors and reproduced through conventional sound equipment-nothing need be changed. But the show will not be particularly improved.

The picture can also be projected through expander lenses, but, although the image will be larger, its full benefits still will not be realized.

Some Advantages

When played through a horizontal projector the VistaVision image can be made very large without adding distortion; it can be brilliantly illuminated because of the triple area of its frames which accommodates more light and heat without damage to film; and picture grain is greatly reduced because there is less magnification both in the photography and in the projection, owing again to the larger frame size.

Similarly the sound, reproduced through a conventional soundhead, can be played in the conventional way. Reproduced through the Century VistaVision soundhead it can still be played through conventional equipment in the conventional way, but the upper frequency of reproduction will be 16,000 instead of 8,000, provided the amplifiers and speakers can handle 16,000.

However, the sound will not only go up to 16,000 cycles in pitch, it will also become three dimensional (not stereoscopic) if the necessary three channels and a control panel are provided. An inaudible control frequency is recorded in the track; it acts on the control panel (if installed) and automatically adjusts the volume from the three sets of speakers from moment to moment. Thus the sound (albeit the same sound, not three different sounds) appears to originate in different locations, according to the action on the screen.

And the result, new sound and new picture, is a completely new show, beyond all comparison superior in attraction to the old-fashioned movie.

I am proud, that my company had so large a part in bringing this new entertainment into existence; a new pattern of entertainment so wonderful that not only is Paramount using it, but Warners and MGM are reported to be adopting it too. It's a big thing to have had a big share in. But what I am proudest of all is that we did it - mirabile dictu we did it - in four weeks!

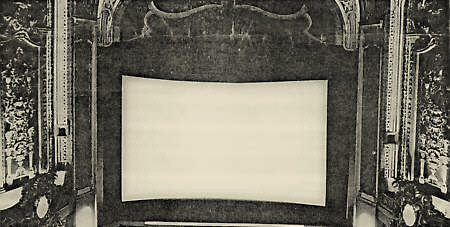

The huge screen at the New York Paramount is seen. The theatre was one of the very first in the country to equip itself for the showing of horizontal VistaVision. The special projectors helped paint the screen with an image that was clear, no distortion, and excellent depth of focus.