Single Film Presentations

Cinerama was unquestionably the most impressive and involving of all widescreen systems developed in the period from 1952 to 1972. But the technical limitations presented by the multi-panel ultra wide angle image did not favor story telling. By 1963 Cinerama, Inc. faced financial problems that would lead to the abandonment of the venerable three strip camera.

| While a number

of films shown under the Cinerama banner were better than average movies

in and of themselves, they were not Cinerama in anything other than name.

It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World was the first film to receive the single

film, single lens projection presentation. It was near completion when

producer / director Stanley Kramer was approached with the offer to showcase

his gigantic comedy on the curved screen. Later films would be photographed

with some consideration for the curved screen but generally single film

Cinerama was just a circuit of theatres |  | |

How do you convert a 70mm Cinerama film into a conventional film? Easy, just change the posters. | |||

Ultra Panavision 70 utilized the same 2.2:1 camera and projector aperture ratio as Todd-AO but the photography was done with anamorphic lenses that added a modest 1.25:1 squeeze. A chart showing a field of squares would look like this, with each square appearing slightly squeezed. |  |

The Ultra Panavision frame as projected with the appropriate anamorphic lens yields an undistorted screen image with a maximum screen ratio of 2.76:1. Note: only Ben-Hur and Mutiny on the Bounty were shown with 70mm anamorphic prints. MGM and Panavision recommended that the screen width be limited to 2.55:1. |  |

For Cinerama single film projection, Ultra Panavision films could be printed with optical "rectification" that removed the anamorphic squeeze and replaced it with a gradient squeeze beginning at the center, with no squeeze at all, and gradually applying a squeeze towards the outside edges that would be naturally removed by the image being projected against the oblique curved sides of the Cinerama screen. The maximum aspect ratio from these rectified prints was approximately 2.6:1 as measured along the curve or just over 2:1 as seen from the back of the theatre. |  |

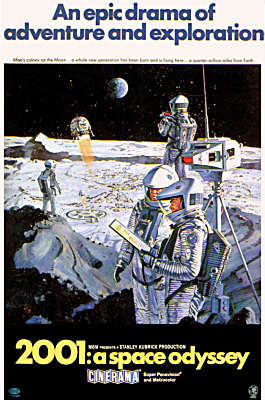

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

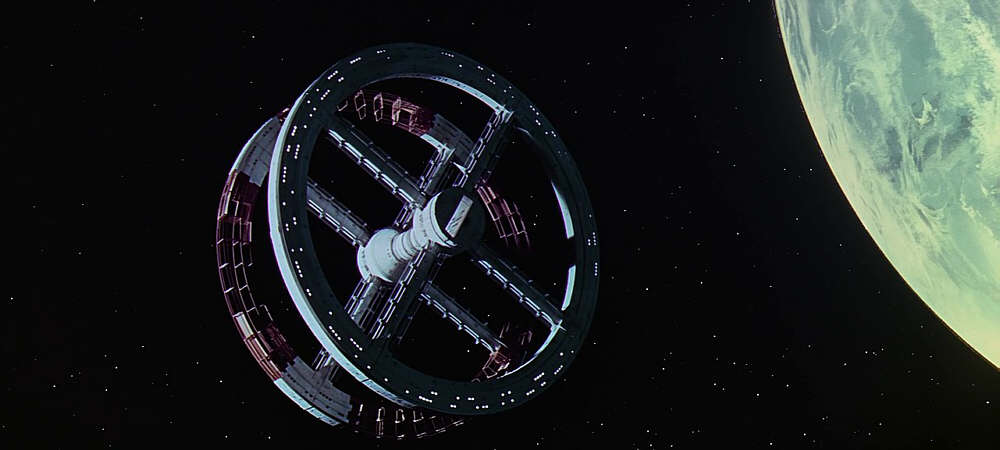

Shown above is a frame from a 70mm Super Panavision 70 print of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Unlike the films made in anamorphic Ultra Panavision 70, spherical films made in Super Panavision, Technirama, and Todd-AO did not receive the optical "rectification" for the curved screen. In actual fact, the rectification process may not have contributed much to correcting screen distortion and the additional optical steps would have presented image degradation problems not faced with a simple contact print.

Courtesy of David Kilderry 70mm frame from a rectified Ultra Panavision/Cinerama print. The black bar running horizontally across the bottom of the frame is a clue that this is an optical print (by Technicolor), even though the side squeeze is not readily apparent.

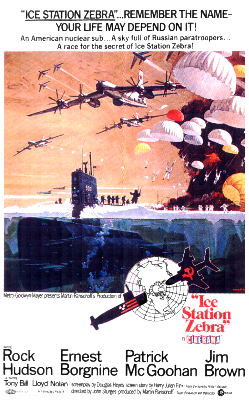

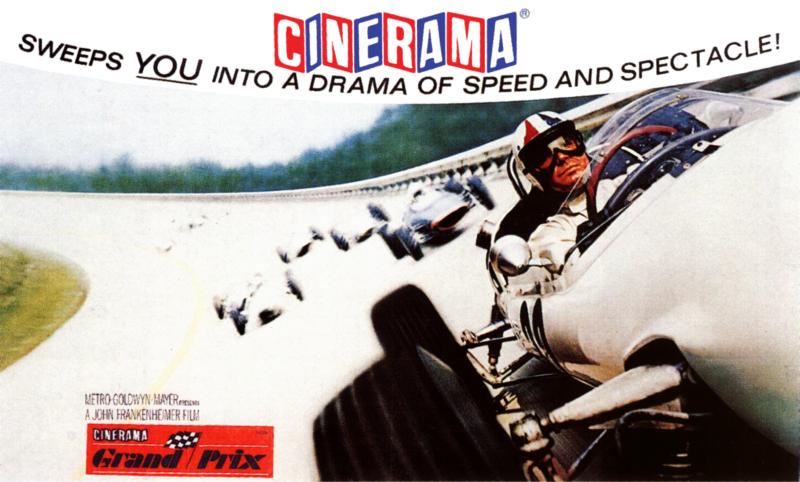

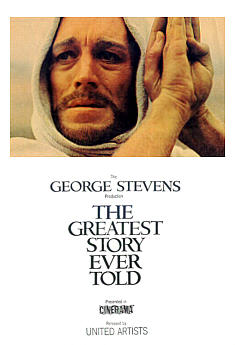

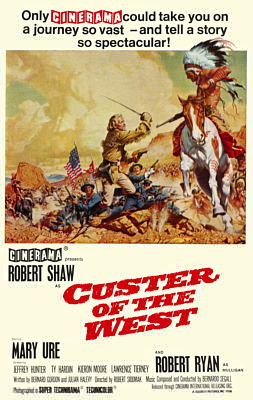

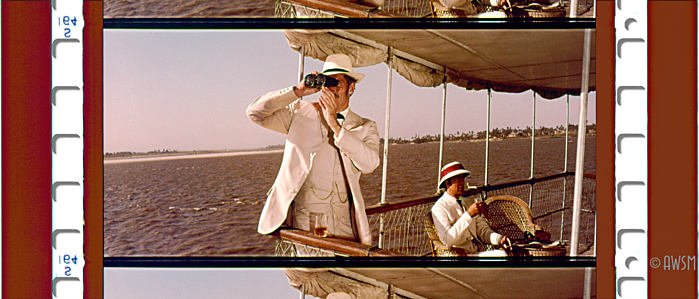

Khartoum, one of the better single film Cinerama productions, photographed in Ultra Panavision 70. Other seamless Cinerama presentations were: The Hallelujah Trail, The Greatest Story Ever Told, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Battle of the Bulge, all done in Ultra Panavision; Grand Prix, Ice Station Zebra, 2001: A Space Odyssey, filmed in Super Panavision, Krakatoa, East of Java filmed with old Todd-AO cameras and lenses, and Circus World and Custer of the West, filmed in Technirama.

At right, Ice Station Zebra, not a bad film, but a screen as large as Cinerama's shows off bad special effects glaringly.A few other 70mm films were shown, from time to time, in various Cinerama theatres but these were not official Cinerama releases. One film, never seen in any documented list, was a promotional film made for Ford's Lincoln-Mercury Division in approximately 1964. The film introduced new models to company stockholders.

70mm film courtesy of David Kilderry

Grand Prix, an uneven John Frankenheimer epic on car racing, used wide angle photography more often than most single film Cinerama presentations. On the other hand, it used extreme telephoto shots more often than the others. The driver's helmet appears slightly stretched, due to the camera lens, and was further stretched on the oblique sides of the curved screen since the Super Panavision films were not rectified to compensate for curvature.

Good intentions and inspiration, millions of dollars, and tons of talent aren't enough to guarantee that a really good movie will result. George Stevens had been planning The Greatest Story Ever Told since 1948. It had been scheduled to be made at Fox in CinemaScope in 1954, in CinemaScope 55 in 1956, in "Grandeur" (probably CinemaScope 55 with Todd-AO compatible reduction prints) in 1958, and finally in Cinerama in 1965. After three days of filming with the 3 strip camera, the production switched to Ultra Panavision 70. The critics were kind, though not ecstatic, and after the churches had sent their congregations to the theaters, attendance dropped off. The film, after all, was boring.

Furthering the boredom, Stevens, for reasons that no one can adequately explain, decided to use substantial amounts of Alfred Newman's score for The Robe instead of original pieces that Newman had written for the production. Newman, like many film composers, was not against borrowing bits and pieces of his earlier works, but in this case, Stevens appears to have elected to use the earlier score for over half his picture. The film has its advocates, but it's still a boring movie.

Poster art courtesy International Film Archive

Good intentions and inspiration, millions of dollars, and tons of talent aren't enough to guarantee that a really good movie will result. And Custer of the West didn't have any of those traits. Had it not been for Krakatoa, East of Java, this monstrosity would have been known as the worst film ever shown as a single film Cinerama presentation. Now it's almost totally forgotten. Like Krakatoa, Custer of the West was produced by ABC (the TV guys) and Cinerama Releasing Corp. Spain substituted for the American West, decidedly not too similar to the Black Hills of South Dakota. Top notch British actor Robert Shaw played Custer, and he also wrote several songs for the film. His acting was superior to his song writing. ABC and Cinerama Releasing produced a third and final large format bomb, Song of Norway, a film so awful that it wasn't actually released, it escaped. Song of Norway was not an official Cinerama presentation, though it was shown in a few Cinerama theatres.

Poster courtesy of Roland LatailleMake no mistake about it, this thing was a huge stinker. The fact that Krakatoa was actually west of Java, before the explosion, was the least of its problems. And with Krakatoa, East of Java the era of Cinerama presentations came to an end.

Pacific's Cinerama Dome

Cinerama was an East coast invention and company. Hollywood and the creative community were West coast operations. The West coast never really grasped Cinerama, even after the company was acquired by California based Pacific Theatres.

The single strip era began with the premiere of It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, World at the Dome which, supposedly, was capable of showing three strip films. Unfortunately for Southern California audiences, this new landmark was poorly designed and even single strip films were not shown at their best. After over 35 years, the company has renovated the Dome and installed real three-panel projection. Presentation of Cinerama films is exceptionally good, owing to great care in assembling the various components. Pacific's Cinerama Dome is now part of a new complex, dubbed "Arclight", with a multiplex of conventional theatres, restaurants and souvenir sales. It's THE place in the Los Angeles area to see a movie.

Today a wave of enthusiasm is running around the globe as interest in resurrecting the three-eyed monster grows. Bradford, England, Seattle, Washington and the Dome are now capable of running three strip films. Can a mere seven productions, made over a single decade, provide incentive to dust off the remaining three-eyed cameras so that new films can be made? Probably not. It's impressive but it's expensive.

-360°

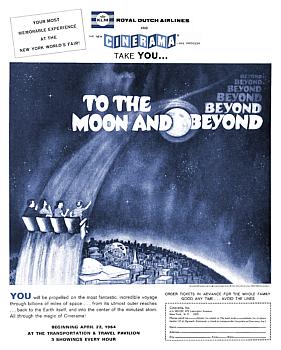

at the 1964 New York World's FairLife magazine ad and ticket order form for To The Moon and Beyond in the Cinerama 360° system. It's quite likely that this was one of the inspirations for Omnimax. Those reserved seat tickets would set you back 25¢ each.

Ad artwork courtesy of Don Griffiths Excerpt from "Business Screen Magazine" A Pictorial Report on Audio and Visual Exhibition Technique at the NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR (1964). Published by ReevesoundCourtesy of John P. Pytlak, Eastman Kodak Company.

|

One of the nation's favorite theatres for any sort of film, not just Cinerama, was the Uptown Theatre in Washington D.C. which always strived to put on a showmanlike presentation for its patrons. In January, 2005, Loew's Theatres, owners of the Uptown, announced that it would no longer utilize union projectionists but instead rely on the "Manager-Operator" scheme, which has guaranteed crappy showings and damaged films in so many of their other showcases. Regular patrons bemoan this change of policy.

One of the nation's favorite theatres for any sort of film, not just Cinerama, was the Uptown Theatre in Washington D.C. which always strived to put on a showmanlike presentation for its patrons. In January, 2005, Loew's Theatres, owners of the Uptown, announced that it would no longer utilize union projectionists but instead rely on the "Manager-Operator" scheme, which has guaranteed crappy showings and damaged films in so many of their other showcases. Regular patrons bemoan this change of policy.

Ticket courtesy of Larry Karstens

and we can't believe he bought a balcony seat for a Cinerama showing, even if it was just 70mm.

E-mail the author

CLICK HERE

©1996 - 2010 The American WideScreen Museum

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com

Martin Hart, Curator

to the MOON

to the MOON Left: a moving stairway takes viewers up to the dome theater for Cinerama "Moon" journey.

Left: a moving stairway takes viewers up to the dome theater for Cinerama "Moon" journey.

Right: Scene from Graphic Films' production which explores the vast events out beyond outer space

Right: Scene from Graphic Films' production which explores the vast events out beyond outer space