For 13 years this image appeared at the start of some of the greatest widescreen films ever made.

Listen to the Alfred Newman's Fox Fanfare for CinemaScope

WINDOW'S MEDIA (WMA) FORMAT

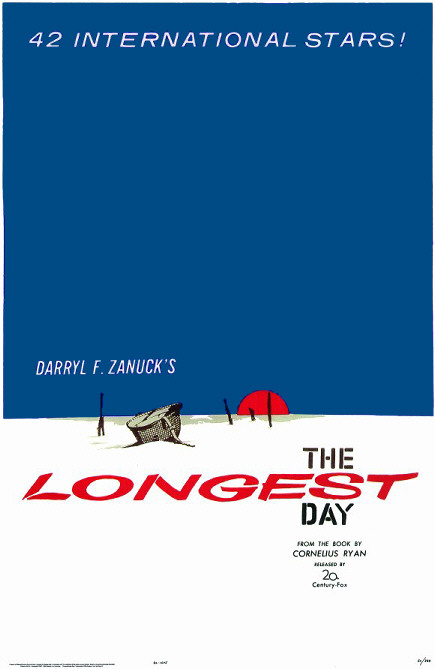

Daryll F. Zanuck wearing an unofficial director's hat in addition to his official position as producer of The Longest Day, in CinemaScope, the most expensive black and white film made until Schindler's List three and a half decades later. Zanuck was a true icon in the film industry, driving 20th Century-Fox through their most productive and successful years. We'll let Mr. Zanuck wear whatever hat he wants while we take ours off to him.

The pioneering work on anamorphic 35mm widescreen spearheaded by 20th Century Fox president Spyros Skouras, vice president Darryl F. Zanuck, and their technical staff set the standards by which all similar systems conform up to this day.

Throughout the 1950's other studios adopted CinemaScope compatible widescreen systems. Little Republic Pictures bought a fistful of anamorphic lenses in France and produced "Naturama" films. Warner Bros. likewise acquired anamorphic lenses and released several pictures in "Warnerscope". Even 20th Century Fox, who had stated that all CinemaScope pictures would be photographed in color, made several in black and white and called them "RegalScope". Later they would revert back to the CinemaScope trade name even for black and white.

A small company by the name of Panavision began producing anamorphic projection lenses in the early 1950's to meet the demand as more and more theatres adopted the CinemaScope format. A close relationship with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer brought them into the business of designing camera optics and ultimately cameras. A vastly improved CinemaScope lens was awarded an Oscar and gradually found its way into the production of more and more films. While Fox still licensed the use of the CinemaScope trade name, MGM and other studios adopted the Panavision lenses over the last part of the decade.

Ultimately, as more and more studios closed down their in house camera departments, the Panavision lens and cameras came to the forefront. In 1967, 20th Century Fox abandoned the use of their Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope lenses and began using Panavision for their anamorphic films.

One of the last films to carry the goose bump raising CinemaScope logo, Stagecoach, produced by Martin Rackin and directed by Gordon Douglas in 1966, featured a star studded cast but it pretty well fizzled. On its own it might have been more favorably reviewed but being a CinemaScope - Color by DeLuxe - Stereophonic Sound remake of a screen classic, it just didn't cut the mustard.

The End Of An Era

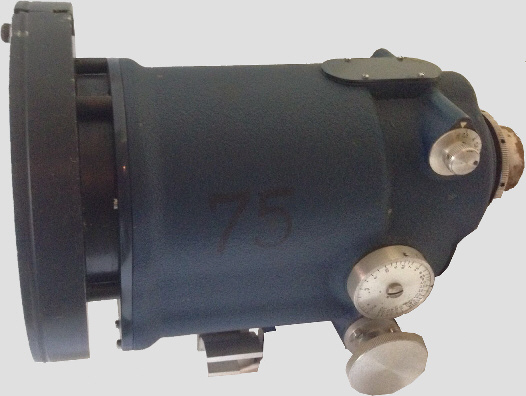

I have included photos of both sides of this 75mm lens to show you how different they are.Nameplate.

In 1967 the curtain rang down on the trusty Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope lenses after the completion of a pair of "spy thrillers"In Like Flint, a typically amusing romp with charismatic James Coburn in the title role of an American secret agent, and Caprice, starring Richard Harris and breathy Doris Day in a suitably forgettable picture. While Flint was no great competition to Sean Connery's James Bond, he was a lot more entertaining and funny than Dean Martin ruining the Matt Helm series over at Columbia. As for Caprice, it was no great competition for any film and its sole distinguishing element is that it was the final film to be released as a 20th Century-Fox CinemaScope Picture.

In Like Flint poster art courtesy of Karl Setnik

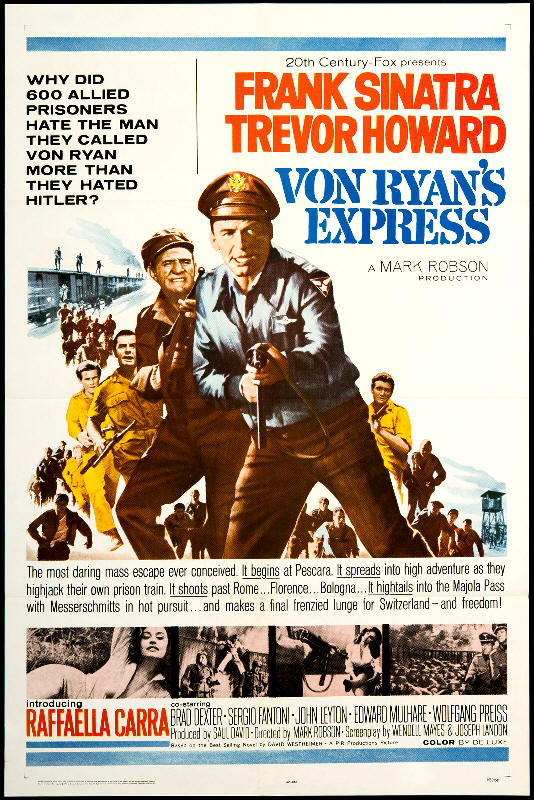

The most enigmatic of all CinemaScope films. You may note that there is no mention of CinemaScope on the poster. While listed as a CinemaScope production, we're told that star Frank Sinatra insisted on the use of Panavision lenses, at least for his scenes.

A CINEMASCOPE PICTURE

is replaced with

Filmed in Panavision

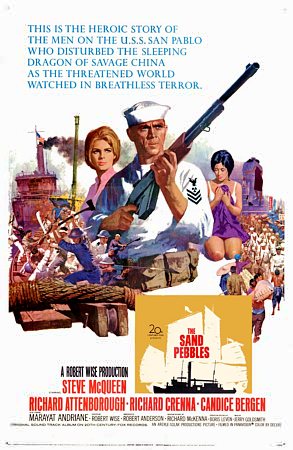

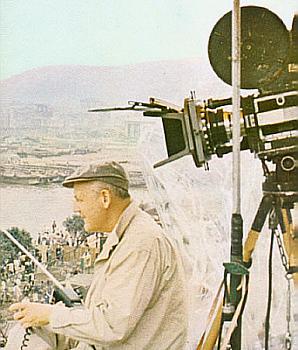

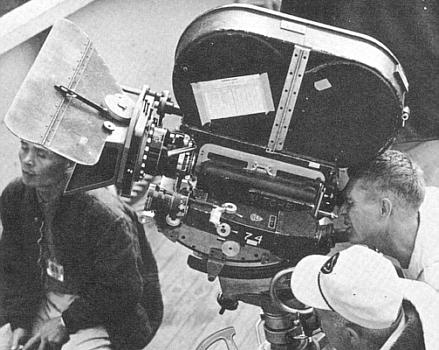

At left, Robert Wise directing The Sand Pebbles in Taiwan, one of 20th Century-Fox's first Panavision films. The film was initially released in road show presentations. At right, Steve McQueen peering through the lens of a Mitchell BNC fitted with Panavision, rather than Bausch & Lomb anamorphic optics.

In 1957, Panavision Inc. introduced the Auto Panatar compact anamorphic lens, which ultimately became the de-facto standard in high quality motion picture optics. Film historian Rick Mitchell, who has heavily researched the subject, provides us with a bit more insight into Fox's move from CinemaScope to Panavision:

"While THE SAND PEBBLES may have been the first film credited to Panavision to go into production, the first to be released was the Parisian made HOW TO STEAL A MILLION, which opened in the summer of 1966.

"However, according to sources at Panavision, most of the principal photography on VON RYAN'S EXPRESS (1965) was shot with Panavision lenses at the insistence of Frank Sinatra, who, along with John Wayne, had been a big booster of Panavision. (The Sinatra co-produced A HOLE IN THE HEAD (1959) was the first 35mm feature to be solely credited to Panavision.) A close examination of a 16mm anamorphic print of VON RYAN reveals some shots that have 'anamorphic mumps' but all the scenes with Sinatra look like films shot with Panavision lenses in the same period."

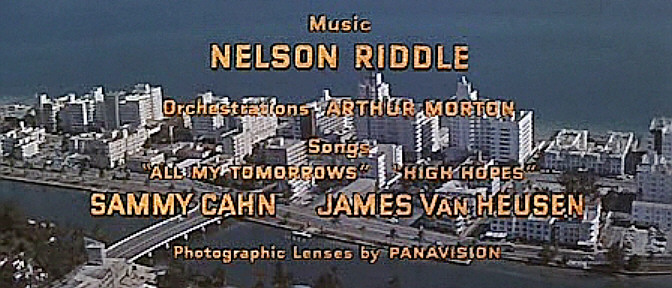

Our friend Rick slightly misspoke regarding the credits for A Hole in the Head. He can be forgiven because he got so much more spot on correct. As can be seen in the poster at left, CinemaScope and Fox's DeLuxe labs are credited. But the actual film carries a credit for neither CinemaScope or Color by DeLuxe. The only process related credit appears at the bottom of this frame from the beginning of the film.

During the period of 1959-1961 there were a number of films that had similar process credits. Just to name a couple, The Unforgiven, and Come September which advertised "photographic lenses by Panavision" on its posters. Then there's the confusing Panavision credit in Spartacus which made people think that Panavision made the Technirama camera lenses.

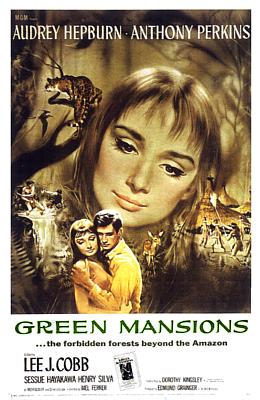

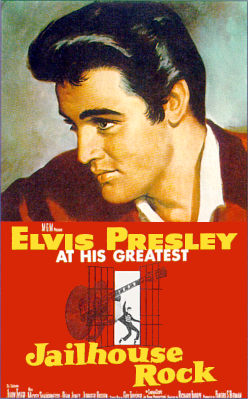

As Rick points out, William Wyler's How To Steal A Million was the first Fox production to be released carrying a 'Filmed in Panavision' credit. The film starred Peter O'Toole and Audrey Hepburn. By a not too surprising coincidence, Hepburn happened to appear in MGM's Green Mansions, (1959), which is frequently referred to as that studio's first picture shot with Panavision optics. However, other films are sometimes credited as MGM's first use of Panavision, including Jailhouse Rock, (1957), the Elvis Presley 'classic' shot in black & white.

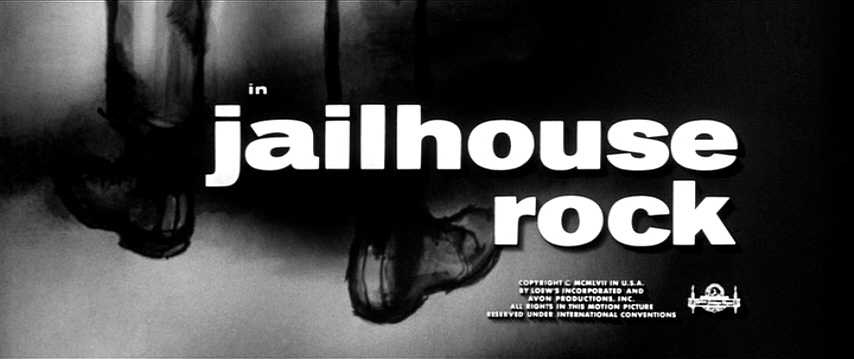

But even though Jailhouse Rock carried both CinemaScope and Panavision credits, it was actually not photographed in either widescreen system. It would have been more correct to say it was a Superscope production since the image didn't become anamorphic until the prints were made through Panavision's MicroPanatar printer lens. Seen below are credits from the film. "Process Lenses by Panavision" indicates that anamorphic printer lenses were used to make CinemaScope compatible show prints. For anamorphic photography the credit would say "Photographic Lenses by Panavision".

Green Mansions poster art courtesy of Karl Setnik.If you're going to make a movie in fake CinemaScope you might as well include fake stereo sound. Note the "Perspecta Sound" credit line. (Bottom line, third frame above.) MGM made a large percentage of their product available with Perspecta encoding. More important films were also available with four track magnetic sound.

While the major studios began to adopt Panavision for their anamorphic films, the trusty old Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope lenses didn't disappear. They gradually made their way into the hands of independent film makers and continue to be used to this day. And your Curator has a couple of them which he sleeps with.

You are on Page 8 of

E-mail the author

CLICK HERE©1996 - 2013 The American WideScreen Museum

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com

Martin Hart, Curator