The CinemaScope Wing is dedicated to our good friend Rick Mitchell. He was one of the good guys.

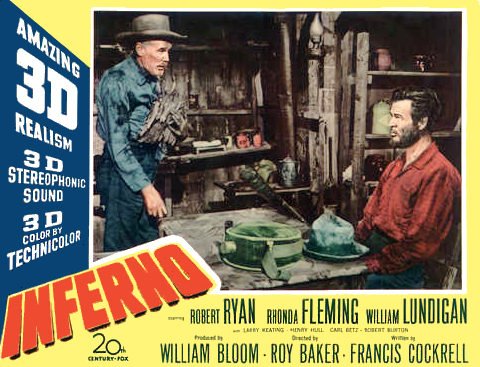

The first departure that the Hollywood based film industry made from the conventional Academy format was 3-D. The biggest studios had the least participation, with MGM, and Warner Bros producing only a few films each. The independents and smaller studios, such as Paramount, Columbia and Universal-International, produced a good many more and they were the sort of films that would have been bombs without 3-D to draw in the crowds. At 20th Century-Fox, Darryl F. Zanuck had complete faith in the wide screen system his boss, Spyros Skouras, acquired in Paris, thus Fox produced but one film in 3-D. Inferno wasn't a bad picture, but it was no worse without the 3-D, and while Fox produced just one "deepie", they were simultaneously shooting three major features in CinemaScope.

One other 3-D film was released by Fox, Panoramic Pictures' Gorilla At Large. Cast and crew were all Fox contractors. Is it any wonder that 3-D came to be associated with schlock?

Despite Fox's participation, minor as it was, in the 3-D craze, something bigger was happening in Paris...

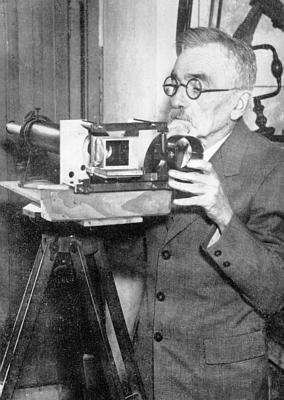

Prof. Henri Chrétien demonstrates his bent glass.

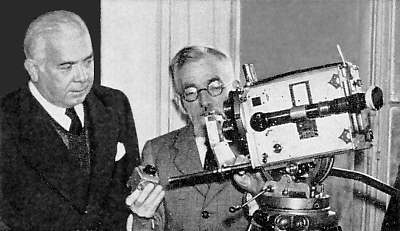

20th Century-Fox president Spyros Skouras in Paris with Chrétien.The rear element of the Hypergonar lens is visible, clearly showing why it was useable only with a very limited range of prime lenses.

If Cinerama was the star that guided the film industry into wide screen presentations, CinemaScope was the rudder that steered the course. Studio executives ran for the doors after seeing Cinerama's premiere in New York. Representatives of 20th Century Fox and Warner Bros. literally raced to France to meet with Prof. Henri Chrétien, the inventor of a filming process that he called Anamorphoscope. Fox beat out Warners by just a few hours, so the story goes. Chrétien had developed and patented his process in the late 1920's. Efforts to interest not only his native French but foreign film makers in his wide screen process had been unfruitful for over 25 years. In fact, his patents had expired. So why were two major studios keenly interested in negotiating with Chrétien? The answer is simple, they needed the lenses that Chrétien had built. Those lenses, which he named hypergonar (nothing to do with overactive reproductive organs), were the basis for the primary surge into true widescreen feature film making.

Chrétien's hypergonar lenses were based on an optical "trick" called anamorphosis, in which an image contains a distortion that is removed with a complementary viewer. In the case of Chrétien's lenses, a horizontal squeeze of 100% was imparted into the image on film resulting in a picture twice as wide as an image taken and projected through conventional lenses. In addition to the anamorphic adapters being used on the motion picture camera, a similar lens on the projector is required to expand the squeezed image on the screen. Pictured at left is an original set of lenses circa 1927. The square lens in the foreground is mounted in front of a conventional 50mm camera lens to provide the squeeze. The projection lens shown has the anamorphic adapter attached to the standard projector lens.

20th Century Fox secured world rights to Anamorphoscope, (with the exception of France and its possessions) and Chrétien's small inventory of lenses. They immediately put them to use in Hollywood by resuming pre-production on The Robe, which had been halted while the old Chrétien lenses were being evaluated. When the film finally went before the cameras it was simultaneously shot in the standard Academy format for release in theatres not equipped for anamorphic projection in addition to the anamorphic lenses, though the resounding popularity of both CinemaScope and The Robe made it unnecessary for the standard version ever to be shown in a theatre. The size of the original anamorphic adapters limited photography to the use of only 50mm and longer prime lenses. Fox presented Chrétien's company, S.T.O.P., with a contract to build and ship additional lenses. There appears to have been delays and quality problems associated with the new lenses and Fox turned to Bausch & Lomb optical company to produce additional anamorphic adapter lenses based on Chrétien's designs.

Camera assistant Lee Crawford demonstrated how the 25 year old anamorphic lens is mounted on the camera during the production of The Robe. The lens must be focused separately from the camera lens.

Even while shooting The Robe, Fox demonstrated their process to the other motion picture studios. Darryl F. Zanuck announced that 20th Century Fox would produce all future films in the new process and invited the other studios to license its use on their productions. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer immediately climbed aboard the bandwagon as did Walt Disney. Shortly Warner Bros., Universal, and Columbia decided to use the new, and as yet unproven, process in major productions. Paramount declined and began work on VistaVision. RKO passed for the time being, as did Republic. Several independent producers also announced plans to shoot some of their planned productions in CinemaScope. Even before the first CinemaScope feature film premiered before paying audiences the success of the system was insured for the next several years. No other technical advance in the history of motion pictures, including sound and color, gained such a high degree of acceptance among American film makers in such a short period of time. Film makers in the U.K. and the European continent were a bit slower to adopt CinemaScope as a mainstream technical advancement, for valid economic reasons following an economically devastating World War, but it wasn't long before the new stretched image became popular despite the costs associated with production and presentation.

Chrétien's company, S.T.O.P., worked to improve their own manufacturing capability after being granted the right to use the CinemaScope trademark in France and its possessions. This appears to be design "B". More modifications were to come just as Bausch & Lomb and other optics companies refined their own designs and manufacturing techniques used to produce anamrophic lenses for both photography and projection.

The word "S.T.O.P." does not mean desist. It's the abbreviation of Chrétien's French optical company, SOCIETÉ TECHNIQUE OPTIQUE de PRECISION. S.T.O.P. was the official manufacturer of CinemaScope camera and projection optics for France and her worldwide possessions, like Viet Nam. Sorry, I couldn't resist that. The significance of that arrangement insured that France's other major early 1950s contribution to the motion picture, Brigitte Bardot, was filmed in CinemaScope with S.T.O.P. lenses.

Here we have some examples of French CinemaScope films featuring the most luscious Mlle. Bardot. To be fair and balanced, Bardot also did some VistaVision films, typically French-British co-productions made by Rank.

From the LIFE Magazine archives

The sole Chrétien made CinemaScope anamorphic lens used to photograph The Robe is seen mounted on a Fox Simplex silent camera.For purposes of clarity, the lens is shown positioned slightly away from the Baltar prime camera lens. In use the anamorphic adapter is slid right up to the Baltar to preclude any light shining in between the two optics which could kill image contrast and potentially ruin a shot.

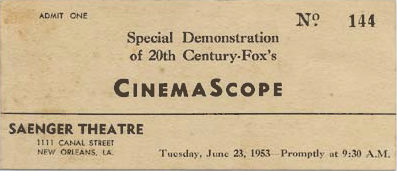

Courtesy of William HooperIf you happened to have nothing better to do at 9:30AM on June 23, 1953, you might want to run down to the Saenger Theatre in New Orleans to see that CinemaScope demonstration. The demo would have been to the then existing specifications of a picture measuring 2.66:1, using the full 35mm silent aperture, and the sound would be 3-track interlock stereo. Literally within days Fox would be experimenting in-house with a new print format combining picture and 4-track stereo sound on a specially perforated film.

Selling CinemaScope Fox's big gamble on CinemaScope required the use of salesmanship of the highest order to get tight fisted theatre operators to go into hock to support the new system. Everything that made up the motion picture theatre was going to have to be changed out. Fox's engineers and their suppliers did everything possible to make CinemaScope backwards compatible with the technology that had been the standard since the late 1920s.

Below you can select to view either of two of Lichtman's promotional announcements for the trade.

Click either image to view larger copies of the documents.

While Zanuck was doing the selling job in the U.S., Fox chairman Spyros Skouras handled areas outside North America. Skouras was self-conscious of the heavy Greek accent that colored his English and was more comfortable handling public events in Europe.

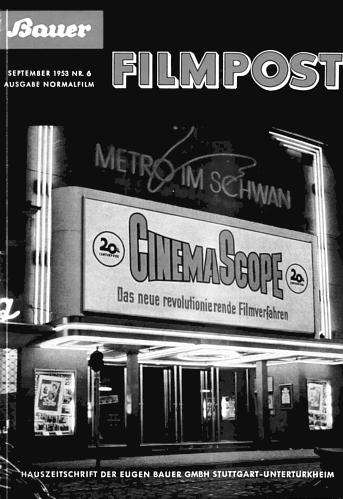

At right is the cover of The September, 1953 issue of Bauer Filmpost. According to Christian Appelt, who provided the photo, "It shows the METRO IM SCHWAN cinema in Frankfurt on the Main where the Fox CinemaScope demonstrations took place on August 25 to 27 1953. The booth was equipped with Bauer B12 projectors fitted with unmarked Hypergonar anamorphic adapters, Spiros Skouras attended the showings and talked to German film technicians and theatre owners.The marquee has a rather strange CinemaScope logo, the subtitle says 'The new revolutionary film system' ".

The CinemaScope logo seen on the marquee was used by Fox prior to standardizing on the more familiar logo.

Photo courtesy of Christian Appelt

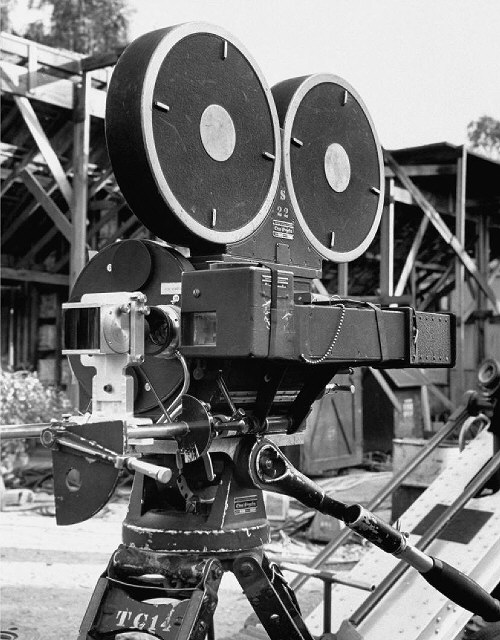

Above left, a Fox camera is pictured with the Bausch & Lomb anamorphic adapter lens, which incorporated significant improvements on Chrétien's original design. To its right is the same camera fitted with a 50mm combination anamorphic lens which allowed simultaneous focusing of the anamorphic and spherical elements, reduced distortion, transmitted more light, and were available in a wider range of focal lengths than could be used with the adapter. Clearer photos of the Bausch & Lomb auxiliary and combination lenses appear on subsequent pages.

While preparations for production on The Robe progressed, the studio had not yet finalized all aspects of their new process, dubbed CinemaScope. The word "Cinemascope" was already a registered trademark for a video product. An expenditure of $50,000 bought the name for 20th Century-Fox. Initial plans, and photography on The Robe, consisted of returning to the original full frame 1.33:1 silent camera aperture, which would provide a projected image with an extremely wide 2.66:1 screen ratio. Sound, like Cinerama, would be carried on a separate 35mm magnetic film synchronized with the picture projector. The stereophonic sound consisted of three channels behind the new wide screen and a forth channel fed speakers on the side walls and rear of the auditorium. By the time The Robe was ready to premiere, the system had been altered to include the sound on the picture film in the form of four magnetic stripes, two located on either side of the picture and two outside the new reduced width sprocket holes, (which were dubbed "Fox Holes"). The magnetic sound striping on many CinemaScope and other widescreen formats was done by Reeves Soundcraft, owned by Hazard Reeves, the man responsible for Cinerama's impressive stereophonic sound system. As a touch of irony, Reeves, then president of Cinerama, Inc. as well as his other ventures, was awarded a technical Oscar for the development of the magnetic striping used on CinemaScope films. He did not receive an Academy Award for his substantial involvement with Cinerama. While a good many companies competed with Reeves to produce magnetic sound stripes on films, Reeves' process had the unique advantage of having the stripes actually stay on the film.

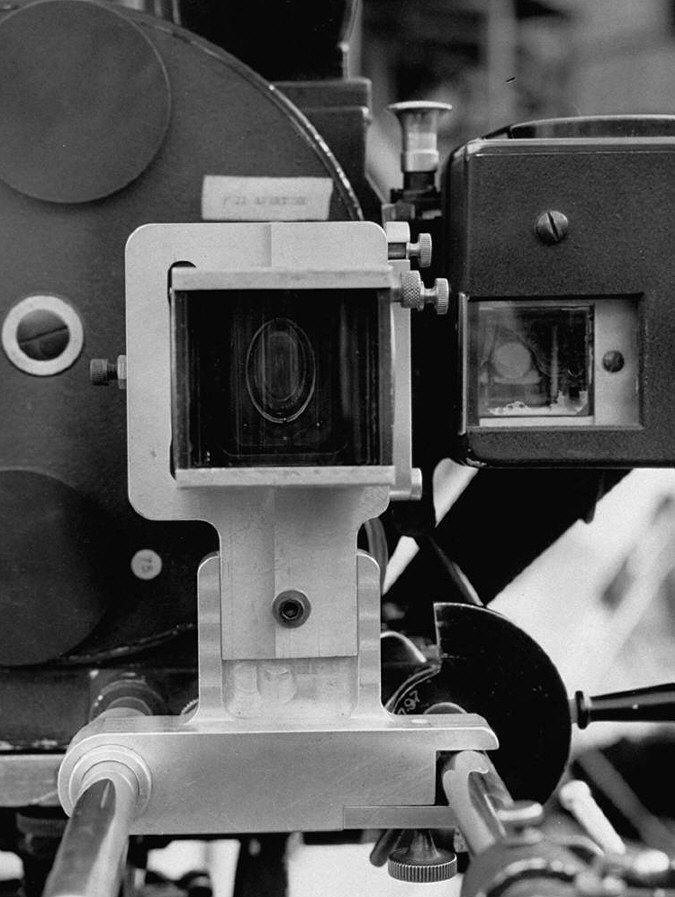

Looking into an anamorphic lens

Peering into an anamorphic lens shows that it magnifies (projection lenses), or compresses (camera lenses) the image only in one direction. While all the elements in this Bausch & Lomb CinemaScope projection lens are round, they appear more and more elliptical as light passes through one element to the next.

Make no mistake, the introduction of CinemaScope was a critically important event in film history. It was the first viable weapon in the effort to get audiences back into theatres. Seen above is the special CinemaScope marquee mounted at the front of the courtyard at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood.

Click Here For A Simple Answer To What Should Be a Simple Question

E-mail the author

CLICK HERE

©1996 - 2013 The American WideScreen Museum

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com

Martin Hart, Curator