These images, provided by John N. Whittle, were part of a Technicolor display made to show how their process worked. It is difficult to tell whether there is any dye fading, though the dyes typically used in system two were relatively stable. The title of the film from which these samples were taken is not known.

Seen top left is the red record, printed and tinted with a green-blue dye. Top right is the green record, printed and tinted with a red-orange dye. At bottom is the cemented composite print. It is understandable why Dr. Kalmus would later decide that the company would print framelines on the base film when they went to three color printing.

It was 1923 before Kalmus could convince a major studio to produce one of their own films using the Technicolor process. Up to that time, and for several years to follow, the majority of Technicolor features or sequences were done solely at Technicolor's risk, and under their complete control. If a studio didn't like the color footage then it wasn't out a substantial sum. In November of 1923, Jesse L. Lasky at Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount) signed a contract with Kalmus to produce Wanderer of the Wasteland, an outdoor western based on a Zane Grey novel. Paramount would shoot the entire film in Technicolor, but would budget no more than for black & white, allow no additional time or resources, or make any other concessions. This was Technicolor's chance to prove that making a film in natural color was not something that was limited just to its own technicians.

Wanderer of the Wasteland, produced by Paramount - Famous Players-Lasky. Seen above is one of many similar movie tie-ins of the era, an edition of the Zane Grey novel featuring photos from the motion picture (in black & white). Note (insert above left) that the Technicolor name was already starting to become recognizable to the public.

Wanderer of the Wasteland required exceptional effort on the part of the Technicolor staff, especially since it was still necessary to ship the undeveloped negatives to Boston for processing and the printing of "dailies". The film proved to be a success and helped shape opinions more in favor of color photography. The western was remade in 1935, in black and white, but with sound. Despite the success of Wanderer of the Wasteland, the studios still weren't ready for major commitments to color.

Over the next few years the cemented two-color process was used in about two dozen films, mostly in key sequences of otherwise monochrome films. Some of the best known films to utilize the process were The Big Parade (1925), The Merry Widow (1925), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), and Ben-Hur, (1926). But having the process used in brief sequences was not what Dr. Kalmus hoped for and neither Technicolor nor any of its generally inferior competitors were setting the film industry on fire.

|  |

|  |

The Technicolor inserts used in Ben-Hur were believed long lost until a well preserved print was discovered in Eastern Europe in the early 1980's. Quite likely American audiences did not see some of the footage since the parade sequence, seen above, begins with a group of lovely bare chested women throwing flower petals in Judah Ben-Hur's path.

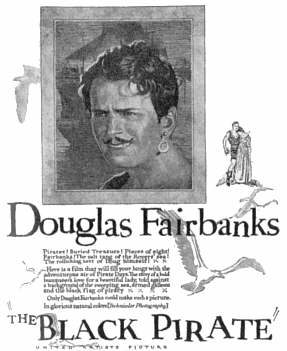

In 1926 Douglas Fairbanks, who had appreciated the quality of the Technicolor subtractive system contracted to produce his big budget epic The Black Pirate entirely in the process. Substantial testing was done to create a palette that was both appropriate and obtainable within the limits of two-color. Despite the extra efforts to shoot a large scale film in color, The Black Pirate got produced and was highly successful, at least for Fairbanks.

Above left - magazine ad for The Black Pirate, above right - lobby card. Douglas Fairbanks' name was a bigger guarantee of box office appeal than any of the imperfect color systems. While Fairbanks was happy with the color, you can see in the inset above the sort of billing that the natural color photography by Technicolor merited.

Technicolor, never having had experience with a large scale film in such wide distribution, suddenly discovered a minor annoyance on earlier films had become a severe problem that would eat away at any profits that might have been made. Since the print was actually two strips cemented back to back, the side facing the projector's arc lamp would heat up and expand more than the side towards the lens. This caused the film to "cup" and replacement reels were constantly being supplied while the folks back in the lab "ironed" the cupped reels flat. Kalmus knew there was more work to be done.

Seen at left is a composite we made from a photo of a pair of negative frames from The Black Pirate. The color shown is relatively close to the original cemented prints. The fringing seen in the image is the result of the source materials being taken from two adjacent frame pairs rather than being from a single pair. No fringing was present in the actual prints.

|  |

| |

System 3

Subtractive Two-Color Dye Transfer Prints

1927-1933

System 3 inherited most of the technology from system 2, but much of it was used in a far different way. The camera was the same, but instead of producing a duplicate negative that generated the matrices that would be dyed and cemented, the matrices were optically generated from the camera negative and were used to make other prints. No more would a matrix film leave the Technicolor plant for projection.

A frame from The Viking (1928), the first sound feature (music and effects only) in Technicolor.

The film was produced by Technicolor and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

The new process which eliminated the cupping that plagued system 2 used the matrices to transfer the dye to a specially prepared clear base film. The ground breaking dye transfer process won substantial acclaim and Technicolor's output increased markedly from 1928 through 1930. During that period Technicolor also had to accommodate the addition of sound on film for those studios that had adopted the Movietone (variable density) or RCA Photophone (variable area) sound systems. Warner Bros.' Vitaphone system did not require any special handling since the sound was on discs. The largest user of the system was Warner Bros.-First National which produced more than 15 Technicolor features in 1930 alone, with 11 of them being full color rather than merely color sequences.

Business dropped to nearly nothing in 1931 and fell even further in 1932 as the Great Depression took a stranglehold on the world economy and theatre patronage began to decline. Audiences had become apathetic of the limited palette color systems and were more than satisfied that their favorite film stars could speak and sing for them. In 1933, Warner Bros. produced their last, and many agree, the best Technicolor two-color feature film, Mystery of the Wax Museum, seen below. The color was substantially better than the illustrations would have you believe.

Mystery of the Wax Museum was long thought to be lost forever, like most of the nitrate based films produced up until 1950. A good quality print was discovered in Jack L. Warner's home following his death. Today a surprising number of these early color efforts survive in the film libraries of Warner Bros, MGM, Universal and Paramount. But even after being copied to modern materials we find that their survival is not assured. Seen in the frames above, the gams on the flapper belong to the movies' top screamer of the 1930's, the beautiful Faye Wray. A horribly disfigured Lionel Atwill, as accomplished at being a heavy as Miss Wray was at screaming and looking threatened, is obsessed by the lady. No one can blame him. Mystery of the Wax Museum is an excellent film with high production values that is highly recommended to anyone. It was remade as Warner's classic 1953 House of Wax in 3-D and Eastmancolor by the WarnerColor labs. The frames are from Scott McQueen's excellent American Cinematographer article on the film from the April, 1990 issue.

Above left, poster for Mystery of the Wax Museum reflects the lax enforcement of the Motion Picture Code between 1930 and 1934. Note that Warner Bros. obviously felt that a bit of breast was a bigger draw for an audience than Technicolor, which is not even mentioned in this poster.

Poster courtesy of the Setnik Collection

Whoopee! (1930), starring Eddie Cantor.Another excellent production in the fully developed two-color Technicolor. This film, along with Mystery of the Wax Museum were considered by Herbert Kalmus to be the very best examples of what was capable in the two-color system.

Poster courtesy of the Setnik CollectionDue to the similarities of the two-color and three-color dye transfer processes, we will discuss printing in the next section.