|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

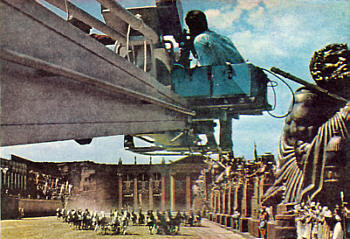

There may have been some disappointment on the part of Robert Gottschalk and his crew at Panavision that Raintree County was not showcased in a 70mm roadshow run. In late 1957 he announced the creation of a new division of the company that would independently produce 65mm films for roadshow treatment. The first film, slated to go before the cameras in May of 1958, was to be The Magnificent Matriarch from a novel about Hawaii, which was to be produced by David Lewis, who had just completed Raintree County. It would include scenes of volcanic eruptions and the first large format underwater shots made with a new 20 pound hand held camera. The announced aspect ratio was to be about 3:1, (indicating that producers still felt that unstriped 65mm prints would be preferable to 70mm mag prints in 1957), and Gottschalk stated that his system would not be allowed to be installed in theatres that could not use a minimum screen width of 60 feet. Furthering Panavision's involvement in the 70mm theatrical equipment field, the company introduced the Ultra Panatar variable anamorphic lens that could be used with either 35mm or 70mm films, and they marketed a 35/65/70 conversion kit for Simplex XL 35mm projectors. (The 65mm components would never see use in any conventional theater.) The Magnificent Matriarch never came to be and the new Ultra Panatar lenses would never be used with 70mm film because new fixed ratio projection lenses were ready for use when Ben-Hur premiered in November, 1959. The new Ultra Panavision 1.256x anamorphic projection attachments allowed much more light on the screen than the variable squeeze lenses.

At right: the Panavision 35/65/70 conversion of a Simplex XL 35mm projector. The magnetic sound system was designed and manufactured by Magnasync. New screens were developed by Radiant, a company that had originally distributed Panavision's products to the industry in the early 1950's, and lamphouses were supplied by Ashcraft. A triple blade shutter was included in the conversion kit to reduce screen flicker. The Ultra Panatar lens is visible to the extreme right. While the Ultra Panatar was adequate for 35mm anamorphic projection it wasn't optimum for anamorphic 70mm so a new projection adapter was developed for the roadshow presentation of Ben-Hur. This is the Ultra Panavision anamorphic projector adapter shown mounted to a small Steinheil prime lens which Panavision provided to theatres that didn't already have 70mm projection before Ben-Hur opened.  The lens pictured above was shipped to the Coronet Theatre in San Francisco on December 14, 1959. From the AWSM collection. Information courtesy of David Kenig-Panavision

Messala (Stephen Boyd) hated Judah Ben-Hur so much that his eyes changed from brown to blue during the race.

Read the complete text of the Ultra Panavision article written for |

©1996 - 2013 The American WideScreen Museum

http://www.widescreenmuseum.com

Martin Hart, Curator