|

|

|

|

|

|

| Billy the Kid produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1930 and directed by veteran King Vidor, advertised the fact that it was a sound picture and ignored the fact that it was filmed in MGM's 70mm "Realife" process. The cameras used on this and the few other Realife films would sit dormant for 25 years before being modified by Mitchell Camera Co. and Panavision to supplement the newly built units for MGM Camera 65. Poster courtesy of Karl Setnik |

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, while simultaneously working on their own approach to wide screen photography, immediately allied itself with 20th Century-Fox in adopting CinemaScope. In fact, in late 1953 and 1954 the two studios ran races to release competitive pictures with similar story lines that took advantage of the wide screen potential of CinemaScope. Due to some of the shortcomings of CinemaScope, MGM also continued its own research into the development of a high quality wide screen photographic process.

Los Angeles Herald & Express

Monday, April 27, 1953

M-G-Mís Arnoldscope

Amazing New ProcessBy JIMMY STARR

Motion Picture Editor of the

Evening Herald and ExpressHollywood now has more wide screen and optical systems than you can throw another dimension at, but M-G-M's top secret at the moment is Arnoldscope, a revolutionary wide angle and depth process (requiring no Polaroid glasses) that could upset the well known apple cart of many experimental methods. . .

Developed and patented by John Arnold, head of M-G-Mís photographic department, the Arnoldscope photographs horizontally on regular 35mm film scenes two and one-half times as wide as standard vertical filming, then it is optically printed back onto 35mm for exhibition, thus eliminating costly theater projection changesÖspecial cameras are necessary however. . . .

Seen above is the forerunner to M-G-M's entry into the wide screen system parade. Developed by John Arnold in the M-G-M camera department and referred to as the 10-Holer or the inspired name Arnoldscope, the image was similar to VistaVision's 35mm horizontal frame but was extended in width to 10 sprocket holes. In fact, work on the 10-Holer predated the introduction of both CinemaScope and VistaVision. There was concern at all major studios regarding the overtaxing of the small 35mm frame as it was cropped to create a "widescreen" image on large theatre screens. Extensive work was done in the development of large format systems in 1929-1930, with both 65mm and 70mm films being made. Gauges of 63mm, 68mm, 56mm and others were created, but few saw actual use. Additionally, larger format horizontal systems were experimented with and one of those, the Fearless Superpicture system, may have been adapted in the development of 10-Holer. Arnold's camera had interchangeable movements that allowed it to shoot not only 10-perf images but 4, 6, and 8 also. The system was never used to produce a film. Of all the single film systems to evolve during the large format heyday, only CinemaScope 55 would have recorded a larger area negative. The exact reasons for the abandonment of the 10-holer project are not clear, though M-G-M appears to have taken a liking to the 65/70mm concept used in Todd-AO. Statements that M-G-M Camera 65/Ultra Panavision 70 evolved from the 10-Holer are inaccurate. Camera 65 was developed entirely by Panavision, Inc. based on M-G-M's wish list. (See Below)

Above left, a newspaper article from The Los Angeles Herald & Express from April 27, 1953, breaking the news of M-G-M's secret new process. While new patents may have been applied for, the system is actually very closely related to the Fearless Superpicture system developed in 1929.

Courtesy of David Strohmaier

The funny looking box that started it all.

The Super Panatar (also known as "The Gottschalk Lens"), was an adjustable prismatic anamorphic projection attachment that was mounted in front of a standard prime lens. The reason that these and similar devices from Superscope, Hilux-Projection Optics, and others, were made to be adjustable was that there was uncertainty as to what anamorphic systems would be developed. Paramount had announced a variation on VistaVision that would require 1.5x anamorphics and Rank, in Britain, had a slightly different variation that would use 1.3x. When the smoke finally settled however, only the Cinestage 35mm prints of Around The World in 80 Days with their unique 1.567x squeeze would actually materialize (see Todd-AO for details). All other 35mm anamorphic systems standardized on 2x squeeze CinemaScope compatible prints.

Panavision, Inc. was founded to manufacture high quality anamorphic projection lenses to meet the demand of theatre operators converting their houses to CinemaScope. In 1954 as M-G-M began preproduction on a massive remake of their 1925 epic Ben-Hur, Chief of Research and Development, Douglas Shearer, approached Panavision president Robert Gottschalk with a challenge to develop a new, ultra flexible, 65mm camera process. Shearer wanted to avoid the distortions common to the early CinemaScope lenses and also asked that the system should be capable of being printed in every format from 3-strip Cinerama extractions, 70mm anamorphic, 35mm CinemaScope, 35mm flat and 16mm anamorphic. Gottschalk and his staff set to work without any financial assistance from M-G-M.

The Moment of Conception Recently unearthed sketch shows MGM Camera 65 before its birth.NEW!

Historic MGM Memo on the Conception Douglas Shearer Memo to The Boss, Arthur Loew,

The New 65MM MGM Panavision System is Explained

MGM CAMERA 65 Test Footage From 1955 Shooting a new MGM logo and testing lenses

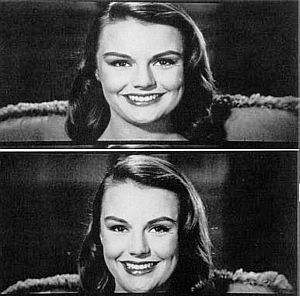

The Problem and the Fix... The problem was called "CinemaScope Mumps", in which the center of the image received less horizontal squeeze when the lenses were focused at short distances. When projected, the center of the image was expanded more than its original compression. In the early days of anamorphic photography close-ups were avoided. When they were deemed necessary, the actor was placed either to the right or left of center where the inconsistent squeeze would pose no problem. It is easy to see what Gottschalk and his team at Panavision were able to accomplish. The upper image is a close up taken with an early Bausch and Lomb CinemaScope lens and the lower image is a 35mm reduction print taken from the newly developed M-G-M/Panavision process. We can thank Panavision that this beautiful woman and all others photographed with anamorphic lenses don't look like broadcaster Cokie Roberts. This promotional photo was produced by M-G-M to promote the new system.

The difference between the two photos is at the same time accurate and deceiving. While the system did yield a CinemaScope compatible print without the distortions of contemporary Bausch & Lomb lenses, in fact the low anamorphic squeeze factor of 1.25x would never have created such distortion had it been applied to the B & L design. By the same token, the prismatic anamorphic design would also never create the distortion even if it was 2:1.

You are on Page 1 of

Read the complete text of the Ultra Panavision article written for

WideGauge Film and Video Monthly